Communion & Poetry

By John H.B. Martin

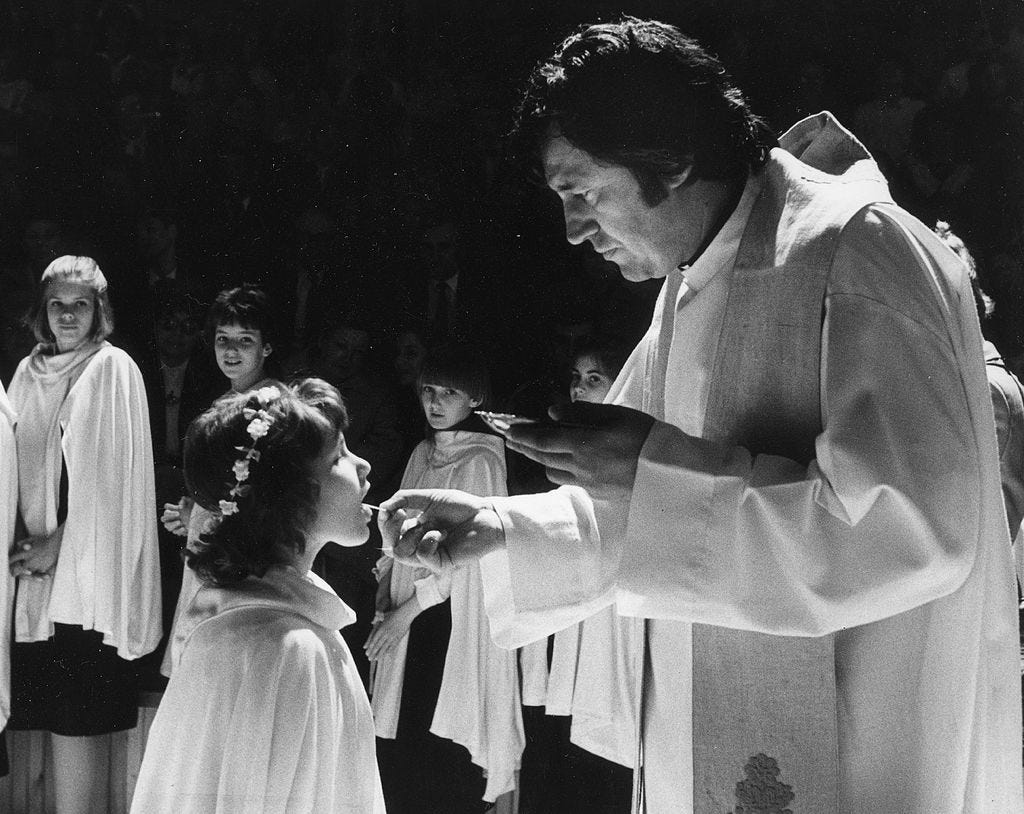

Communion

a nun takes the veil

The mist is frugal, and the forest green

and shady, where thin slats of sunlight weave

that sort of blind which leaves most eyes wide open.

Some sort of woodlark sings from high above

its “fruitless” song, which echoes even in

the depths of every shadow, like a bell

to summon every belle to ecstasy.

I too obey. And line up under one

abandoned pine, to take my cue from thyme

itself, whose scent envelops me in incense,

till each fresh tree seems like some monstrous feast.

They’re not! They’re only trees. (And even I

am only human.) - Please forgive me, lord,

for every crime I’ve mimed, but not committed.

Poetry

Romantic figures stalk the desolate streets

whose actual lives are scarcely that romantic.

How can they be? No life is that ideal!

(Reality must catch up at long last.)

Leave dreams to adolescents and their ilk:

romanticism is a bitter fruit

whose peel is more enticing than its pith

can ever prove, it’s such a devious poison.

Affect the classic pose. It’s not quite prose

perhaps… But it is poetry. Mere childhood's

adventurousness madly lies behind it

just like a dream wrapped in a sacrament…

While, in the foreground, all is calm and ordered

and discipline’s the flavor of the day.

John H.B. Martin is a poet who lives in London, England. He is a graduate of London University and Australia National University and has been writing for many decades. He has written four novels and is working on a fifth. His magnum opus is a six-volume epic poem. Most of his work is yet to be published.

Eurydice, A Vision, The Cave of Making & Other Poetry

Featured in New Lyre Magazine - Summer 2023 Eurydice That was the Sistine Chapel, wedged between our complex life and all that slept beneath your kisses, and my curses, as we danced love's simple dance beneath the midday moon. Which might as well have been the midnight sun

The word play’s a delight

That veils a deeper bite

Mr. Martin's lines transported me to childhood, adolescence and early manhood. My childhood was spent among Dominican nuns in the days before cape, coif, veil, habit and ponderous beads were replaced by the modern fashion of blue jeans and tee shirts. I remember them in their somber, black capes, kneeling in the first rows before the altar at 7:00 a.m. mass. I studied with them and was pruned and shaped under the tender mercies of modern day daughters of the Inquisition.

When I was nineteen I returned to visit an old nun whom I had loved. She received me in a little reception room with two arm chairs and small mahogany tables that showed no sines of use or wear. The room was a living diorama of the election of silence and solitude. At the end of my visit, Sr. Hildegarde took me into the nuns' small chapel, where we knelt in the soft lighting, and shared a prayer. I bever saw her again after that day. Later I found that she had died nine years later. Mr. Martin's poetry evoked memories of that last meeting in the dim lighting and sweet scent of bee's wax candles. No lark was there, only the invisible, silent comfort of a Paraclete that I had left in the shadows of another day.

Mr. Martin ponders the tension between thought and deed. His poem drew me into the silence that bridges memory and reflection.