“For, he who with an impure hand removes

That mystic veil and sacred covering,

‘He’ said the Godhead, will behold the Truth.”

— “The Veiled Image at Sais”

In Friedrich Schiller’s “The Veiled Image at Sais,” an overly zealous youth guided by a naïve curiosity believes himself ready to unveil the sacred Truth. After having his entreaties rejected by an ancient Egyptian hierophant, the boy decides to break into the temple and try to unveil the Truth for himself.

As in the case of Adam and Eve prematurely eating from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil during mankind’s infancy, an inevitable reckoning with irreversible consequences ensues.

The poem ends on a cautionary note for anyone seeking shortcuts to Truth.

The Veiled Image at Sais

By Friedrich Schiller

Struck by a burning thirst for knowledge, a youth

Travelled across ancient Egyptian lands

—to Sais—to breach the secrets of its priests;

He eagerly made all the needed grades,

But still relentlessly kept climbing higher

—The hierophant could barely tame the boy.

“What good is one small part without the whole?”

Exclaimed the eager youth, without a pause.

“For, can the Truth be really more or less?

The way you speak of Truth is as if it

Were nothing more than a mere earthly sum,

As if a question of just more or less.

Surely, it’s something whole and without parts;

The Truth is pure and indivisible!

Remove one note and harmony dissolves,

Remove one color and the rainbow fades,

And nothing will be known, so long as that

One color, or one note, remains absent.

While the priest and the eager youth conversed,

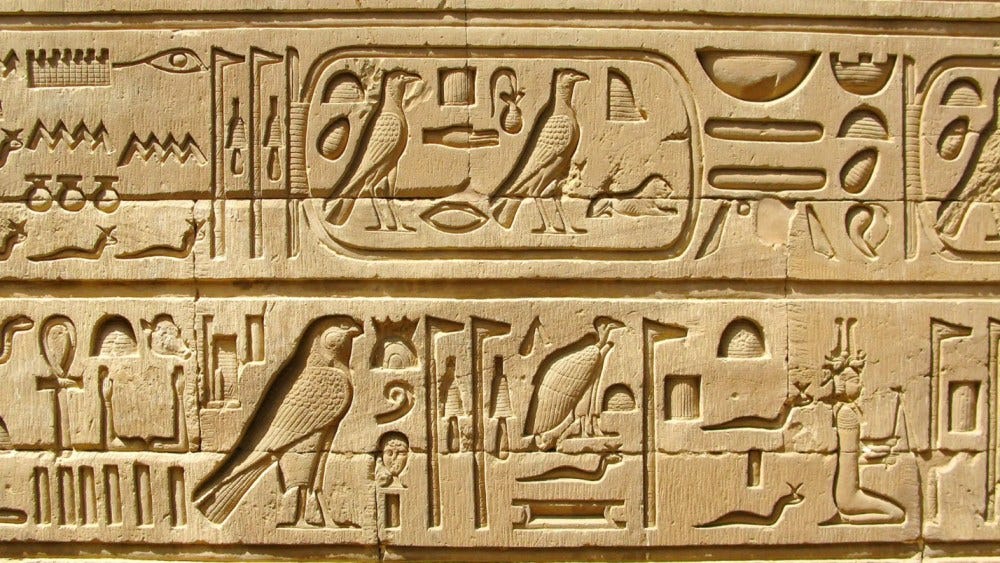

They stood amid the precincts of a temple

Where a strange statue stood silent and veiled.

It captured the excited boy’s attention,

And so he turned towards the wise old priest

And asked, “What lies hidden beneath the veil?”

“Truth,” answered the old priest. “What!” said the boy,

“The Truth alone is all I care about,

And you would think of hiding it from me?”

“Only the Godhead can answer to that,”

Said the Egyptian priest. “And let no man

Reach for that veil,” he said, “Until I do;

For, he who with an impure hand removes

That mystic veil and sacred covering,

‘He’ said the Godhead, will behold the Truth.”

“How strange! And have you never tried to lift

The veil yourself, you who worship the Truth?”

“I never have, I never felt the need.”

“Could it be that only a thin veil stands

Between me and the Truth of things?” he asked.

“And a divine decree,” rejoined the old priest,

“The weight is heavier than you might think;

Though it may seem light to the hand—heavy—

So heavy can it weigh upon the mind.”

Lost in his thoughts, the youth made his way home,

But he now burned with a desire to know.

Restless, sleepless, tossing around in bed,

He rolled for hours, until at last the clock

Struck midnight and he rose, and quietly

Found himself drawn by a powerful force.

He climbed the walls, then after one more spring,

He found himself beneath the sacred dome.

Behold! The child in utter solitude,

Stood amid nothing but the deathly silence,

A silence broken only by the echo

Of every step he took across the vault.

And through the aperture of the high dome,

The quiet moon rained down her pallid beams

Just on the place where shining in the light,

The statue stood, concealed by its long veil.

The boy began to walk towards the form:

Hesitant, he moved his impious hand

Towards the statue, and then suddenly,

A chill ran down his spine; an unseen hand

Repulsed the boy, “What do you want,” echoed

A tortured voice within his shaken breast.

“Would you dare profane the Holiest One?”

“It’s true, declared the oracle, ‘Let none

Venture to raise the veil until I do.’

But did he not say Truth as well would rise?

Whatever it may be, I’ll raise the veil.”

And then he said, “I will behold the Truth!”

“Behold!”

His own words echoed back in mocking tone.

And with that word he cast the veil away.

What form his harrowed eyes met I don't know,

But when the warm, fresh morning's breeze returned,

The priests found a pale and unconscious boy

Lying before the pedestal of Isis.

He never shared what he had seen that night,

From that day on his happiness had fled;

Deep sorrow brought him to an early grave.

When pressed by questioners, he only said,

“Woe unto him, who comes to Truth through guilt:

Delight will forever be lost to him.”

Translation © David B. Gosselin

Reflections and Commentary

Was our young truth seeker really guided by a love of Truth, or merely by a puerile desire to possess the object of his infatuation, with little appreciation for what it might entail or exact? While he was eager to have his demands met, the boy may have underestimated Truth’s demands on him.

As in the case of any serious relationship whose requirements far outweigh one’s abilities or expectations, Schiller’s poem offers us a dramatic rendering of the most demanding and tribulating of all relationships: our relationship with Truth.

His enigmatic lines beg the question: is man ever ready to wrestle with divine wisdom? If so, how should he go about it; if not, how should he guard against its crushing revelations? There are at least some hints in the hierophant’s mention of “impure” hands reaching for sacred knowledge:

“And let no man

Reach for that veil,” he said, “Until I do;

For, he who with an impure hand removes

That mystic veil and sacred covering,

‘He’ said the Godhead, will behold the Truth.”

Not unlike the story of Daedalus warning his son Icarus not to fly too close to the sun, Schiller’s work presents the story of a boy whose curiosity was undeterred by even the wisest counsel. The poem highlights the fate of a passionate but ultimately foolish inquirer whose intentions, while not motivated by any ill-will or a lust for power, were arguably just as misguided as those of a reckless upstart or clumsy thief—and perhaps even more fatal.

In his eagerness to lift the veil, the boy treats the sacred Truth as though it were something he could possess. But was our young wannabe initiate really guided by a love of Truth, or merely by an infantile desire to possess the object of his longing, without paying much mind to what Truth would desire from him? After all, how much control will one have once he breaches the sacred temple and lifts the veil?

The man who exits the temple is never the same as the one who enters it.

Moses and the Secrets of Egypt

Further insight into the question of Egypt, ancient history and the illusive “mysteries” can be found in Schiller’s historical study “The Mission of Moses.” Published in 1790, it presents research and ideas Schiller would have originally delivered in the form of a lecture during his time teaching at Jena University.

Schiller begins by acknowledging the debt modern Western civilization owes to the revelations of Mosaic law.

“Indeed, in a certain sense it is irrefutably true that we owe the Mosaic religion a large part of the enlightenment we enjoy today. For through them a precious truth, which reason, left to itself, would have discovered only after a slow development, the doctrine of the one God, was temporarily spread among the people and maintained among them as an object of blind faith until it could finally mature into a concept of reason in the brighter minds. As a result, a large part of the human race was spared all the sad, misleading paths to which belief in polytheism must ultimately lead, and the Hebrew constitution received the exclusive advantage that the religion of the wise did not stand in direct contradiction to the popular religion, as was the case with the enlightened pagans[…]”

Schiller suggests that Moses’ revelatory wisdom indicated he was likely an initiate of the Ancient Egyptian mysteries. A Hebrew whose people had been enslaved by a corrupted Egyptian society would by a twist of fate become an Egyptian-educated Jew who would have been privy to the highest Egyptian mysteries, and thus have been in the position to spread this wisdom in a new revelatory form among his own downtrodden people.

Schiller writes:

“Here the great hand of Providence, which unravels the most tangled knot by the simplest means, must move us to admiration - but not that providence which interferes with the economy of nature through unfathomable miracles, but through that which gives nature itself an economy which prescribes the achievement of extraordinary things in the quietest possible manner. A born Egyptian lacked the necessary invitation and favor of the Hebrews to proclaim himself as their Savior. A mere Hebrew must have lacked the strength and spirit for this undertaking. So what course did fate choose? It took a Hebrew, but snatched him early from his brute people, and gave him the enjoyment of Egyptian wisdom; and so a Hebrew, Egyptian-educated, became the instrument by which that nation escaped from slavery.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Chained Muse to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.