One might think we have Wordsworth’s theory of poetic art to blame for the creep of Instagram and “street” poetry and the subsequent disfiguration of lyric into meme. In the abstract, there is nothing wrong with Wordsworth’s description of the source of poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” Yet is he in some way responsible for the well-intentioned, but less than middling, contemporary phenomenon Poetry on the Streets?

“Poetry on the Streets (POTS) started by bringing a manual typewriter into public spaces, such as bus stops, street corners, parks, and engaging passersby to stop and write a poem based on a word chosen from a ‘jar of emotions.’”

A laudable goal, perhaps, to court the native wit of the vox populi. Here are three examples:

My only regret in life is my parents not being there for me.

It is a very hard thing to fall hard to addiction.

Everyone has desire/ No one can be without desire.

Is this the transcript of a self-help group? An outtake from someone’s diary? Is the generic banality of these “poetic” sentiments the fault of the prompt from “the jar of emotions?” Or that they were written on the street with no further direction, and the fly-by writers left to rely on maximum faith in spontaneity? Can the universe make us its lyre just because we pray for that, or do you have to be Percy Bysshe Shelley in a trance to make that work?

But let’s not be too quick to point the finger at the Romantics, who were merely trying to start a conversation.

Faria Saeed Khan clarifies that

“Wordsworth says that the emotion is allowed to arise and is witnessed along with the sense impressions, while in the open meditative state it is then thought long and deep ‘recollected in tranquility’ and held in mind until its meaning is communicated. On one hand poetry is the product of feelings, but spontaneous feelings will only produce good poetry if they occur in a person of natural genius or sensitivity, and also if that person has thought long and deep, because such thoughts direct and shape our emotions.”

Long and deep. Recollected in tranquility. Open meditative state. Thinking long and hard about said emotion. In other words, the work of the professional poet or a dedicated, talented amateur. Or even a dogged aspirational acolyte. This is beginning to sound like apprenticeship at the Temple of Apollo. One way or another, even if you’re a natural-born genius, some learning is in order, however and wherever you may acquire it. The idealistic fallacy is that anyone can write a poem. That’s part of the bogus lore of democracy, where anybody can do anything if they just try. Unfortunately for the verbal arts, as opposed to painting or music, because we possess language and use it all day, we fall into the error of believing ourselves naturally equipped to write. Just open your mouth and poetry will fall out.

Strangely, the everyman-without-substantial-coaching credo doesn’t apply to professional sports, which are highly competitive and require a combination of innate skill and rigorous training. One without the other usually gets you nowhere. Just because you caught a few passes in Pee Wee Football or quarterbacked in your rec league, that doesn’t put you in the same literal league as experts who bring the vocation to its highest plane of finesse. And nobody is foolish enough to claim with polemical urgency that the rec league person and the quarterback of the Kansas City Chiefs are “both just football players,” and that criteria of quality shouldn’t be introduced to differentiate the two. Feelings won’t keep the D-line from flattening you.

Why, then is poetry subjected to this ersatz democratization, when in raw point of fact, very few people rigorously read the finished work of even the most skilled practicing poets, and insist instead that it’s unfair or elitist to insist on Wordsworth’s aforementioned requirements? There can be healthy debate about movements, tendencies, and to what extent poetry requires specific formal criteria. That’s called the dynamic movement of literary history. That’s how the shot clock and the three-point line evolved in the NBA, as technical means to bring the art of basketball to a higher level. You try different approaches. That’s what “experimental” poetry is all about; to figure out what works and what doesn’t. How far do we stretch before we disfigure? But we don’t leave such matters in the hands of “the masses.” The practitioners of poetry on the fly can cry snobbery and write whatever they want; but one is not required to recognize their half-ideations as artful. A doodle is a doodle.

In the most basic sense, yes, if you possess rudimentary literacy—not even the capacity to compose complete sentences is necessary—you can write a “poem”; most likely a banal one.

Not that such atrocities can’t occur at any level, in any quarter. Walt Whitman, the great, epic democratizer of long, rolling lines, speaking for everyone, and possibly the inventor of what we now call “free verse,” wrote many powerful and memorable poems. My high school girlfriend as a birthday present gave me a copy of Leaves of Grass with photographs by Edward Weston. I still take that volume out and read from it today, enlivened by its expansive American vistas.

But Randall Jarrell, in “Some Lines from Whitman” had a few tart and defensible things to say about the bard’s defects and overwriting, in spite of his general appreciation of Whitman’s verse.

“The interesting thing about Whitman's worst language (for just as few poets have ever written better, few poets have ever written worse) is how unusually absurd, how really ingeniously bad, such language is. I will quote none of the most famous examples; but even a line like 0 culpable! I acknowledge, I expose! is not anything that you and I could do -- only a man with the most extraordinary feel for language, or none whatsoever, could have cooked up Whitman's worst messes. For instance: what other man in all the history of this planet would have said, 'I am a habitan of Vienna?' (One has an immediate vision of him as a sort of French-Canadian half-bred to whom the Viennese are offering, with trepidation, through the bars of a zoological garden, little mounds of whipped cream.) And enclaircise -- why, it's as bad as explicate! We are right to resent his having made up his own horrors, instead of sticking to the ones that we ourselves employ. But when Whitman says, 'I dote on myself, there is that lot of me and all so luscious,' we should realize that we are not the only ones who are amused.”

None of us is immune, on our worst days, no matter how learned and experienced, from producing such writing. The main thing is to recognize dreck for what it is, and not let it find its way into print. We wouldn’t, nor should we, exempt Whitman from criticism of his formal endeavor—in this case, a risible self-seriousness of tone that leads to embarrassing grandstanding. If your brother-in-law’s fly is open at a cocktail party, it’s best to go ahead and tell him right away, before every last person sees the breach of the breeches. There is massive drop-off, likewise, from Neruda’s brilliant early, ‘worked’ surrealist book of poems Residencia en la tierra, to the cloying, amateurish odes of his late period. (He loved his terrible odes so much he wrote and published three books of them, tripling his crime.) Neruda’s body of work is so large that in his case, we can forgive six or seven middling to awful books, perhaps.

An offshoot of the notion of spontaneous poetry written on the street in the name of the common man is the more damnable practice of poets “of the people,” like Whitman, speaking for everyone, courting a reputation for virtue through their political compositions, with a similar democratic alibi. E.g., they are making mankind better and more likely to perform improving acts upon their fellows. Like occasional poems written for presidential inaugurations (I’m waving at you, Amanda Gorman), protest and nakedly political poems are generally destined to arrive as clunkers, where message dwarfs method. Carolyn Forché’s “The Colonel,” a poem feted in the time of 1980s Central American dictatorships, offers a “surprising” (surprisingly hackneyed and tritely melodramatic) image of a corrupt, psychopathic colonel putting on the table before the poet a sack full of human ears that look like “dried peaches.” With the voice of evil incarnate, he mocks the American visiting poet, saying in telenovela cadence, “Something for your poetry, no?” Even if this ‘really happened,’ it only sells as self-glorifying melodrama: the poet as breathless witness to atrocity. (Who can do nothing except helplessly report evil incarnate in a banal prose poem.)

The seemingly more well-intentioned Denise Levertov comes up equally empty-handed and rhetorical in “Making Peace,” as she tries to puzzle out what poets can do to promote peace.

A line of peace might appear

if we restructured the sentence our lives are making,

revoked its reaffirmation of profit and power,

questioned our needs, allowed

long pauses . . .

This extended metaphor of grammar as social action fails. Peace supposedly is a sentence for each of us to execute, so that “profit and power” are “revoked.” This empty hortatory gesture of a dull metaphor is little more effective than a placard held up declaiming “PEACE NOW!” Levertov’s instructions to “us” are wishful, and it’s not even clear to whom she is speaking. All of humanity? Herself? Other poets? “Might appear” makes for a weak desideratum. This prosy, wistful poem’s only value is to demonstrate the poet’s uncertainty about what she plans to do. Peace is a distant prospect and the poem’s vagueness doesn’t bring us any closer.

If these are ‘the best minds of my generation,’ as their inclusion on the Poetry Foundation website seems to imply, only then can we say that maybe the street poets baldly asserting tautological, self-evident self-help proverbs like It is a very hard thing to fall hard to addiction don’t seem so bad after all.

We all have ethics, good ones or bad ones. And when you have something, you darned sure want to use it. The question remains, however: are our ethics up to the demands of the case? Glossing Aristotle’s ideas on ethics as regards virtue and what makes certain activities worthwhile, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy summarizes his enjoinder that “we seek a deeper understanding of the objects of our childhood enthusiasms, and we must systematize our goals so that as adults we have a coherent plan of life. We need to engage in ethical theory, and to reason well in this field, if we are to move beyond the low-grade form of virtue we acquired as children.” These immortal words apply to the writing of poetry as well, which may be classified as an essential part of a coherent plan of life. One hates to knock childlike enthusiasm, but when a person reaches, and passes, the age of reason, that human being must put away childish things, as the Holy Bible strongly advises, if she or he is to court virtue in the demanding, unforgiving, even merciless, medium of poetry. Big sad feelings and spontaneous overflow of emotion not tamed by proper reflection and the stringency of artistic technique are insufficient to the ethical case.

Which brings us to the most ostentatious degraders of poetics: the Instagram poets. I do not say “the biggest offenders,” simply by virtue of the fact that the pros are often messing things up as badly as the self-styled ‘geniuses’ of social media, the latter not participating in prizes, fellowships, and endowed teaching positions; instead, gauged in number of followers. The fact that they are judged by a single, clear numerical index, the only available evidence that they are indeed famous, not to say important, brings clarity to the situation of who is who. Rupi Kaur and R.M. Drake stand at the top of the mathematical heap. No one thus far, least of all their followers, has made any serious attempt to judge them by criteria of quality to justify this numerical fame. They’re famous because they’re famous, à la Andy Warhol.

The “Instagram poets” (the phrase said as if they were an actual literary movement, rather than a pride of egos), display bad faith in their contempt of the fact that anyone could teach them anything about poetics, and they behave as though they in fact de jure are the “betters.” Their operative belief is the only poetry they ever need to read, or scan, is each other’s mercifully short poems, often consisting of four or fewer brief lines. To even call it poetry is a stretch, for it resembles nothing so much as a meme—because it literally is one! Rod McKuen was pilloried for writing poems as greeting cards with inspirational messages and self-involved, artless, conversational and gauzy riffs on sex and love. But at least there was only one of him. And he did, after all, write the song “Seasons in the Sun.” (Richard Brautigan is exempted because he was often surreally funny, almost Dadaist, and he knew it.) IP poems feature no literary referentiality, only literal self-referentiality. They’re as thin as a hologram of a crepe.

The IPs figure in the millions. They are of interest in the conversation about “virtue” by the fact that they represent a limit case, unconsciously distilling the treacly, phony optimism and do-gooding of their bona fide literary predecessors into “poems” as concise as haiku, albeit with nothing of the best haikus’ sense of image, rhythmic possibility, and air of casual mystery. The IP’s thoughty thoughts, most often of the SNL Stuart Smalley, doggone-it-people-like-me variety, are similar in nature to post-its people stick on their bathroom mirrors to keep from killing themselves, to persuade themselves that they’ll find love again after one last session of therapy or yoga, or simply to get through the day. IP poetry, formally speaking, is bested even by the negligible, singsong comic poems of Ogden Nash, by dint of the fact that the latter have recognizable features such as rhyme (however basic), contain snappy iambs and show a sense of what a poetic line is for. They can even be accused in a friendly way of having a penchant for zingy wordplay that causes mild amusement.

Behold the duck.

It does not cluck.

A cluck it lacks.

It quacks.

It is specially fond

Of a puddle or pond.

When it dines or sups,

It bottoms ups.

The chief motive of these guileless mercenaries of IP is to monetize their emotion—that same emotion “on the street” with which this essay began. In IP world there is no room for skepticism or dissent. Everyone’s individualism is not only laudable and encouraged, but equivalent and in fact self-identical to everyone else’s. If a world swap meet of IP poems were conducted at some imaginary cosmic flea market, everyone would come away neither better nor worse than they arrived with their original poems. The emotions being trafficked are known in advance, rather than explored or arrived at. They were made to be looked at and admired, not analyzed or meditated upon. One glance and you get the obvious meaning of the threadbare statement being purveyed. They are anti-koans.

Spend any amount of time on Instagram and you’ll run across these so-called poems, the dwarf children of the untrammeled precincts of free verse. The culture at large, including aspects of “high” literary culture (or what passes for it) helped produce these modest monstrosities. Many a page of Poetry Foundation, as my provocateur poet friend Kent Johnson taught me (requiescat in pace) could be purged without harm, furthering Aristotle’s ethical case for a stricter notion of virtue.

I have Braveen Kumar to thank for an impish unmasking of this modish pseudo-verse. In his article “The Weird (and Surprisingly Profitable) World of Instagram Poetry,” Kumar describes a process that “started as a joke. It ended in 4000 followers and $1.6k in book sales.” Not that this is any sort of fortune in Insta-world, but the point is made. His article begins:

Poetry once more flows freely in the mainstream. But how did we go from William Blake to R.M Drake? From “Tyger Tyger, burning bright” to this:

the right people will always

find you at the right time.R.M. Drake

Above is the insipid micro-musing, straight off a sales meeting whiteboard, of the second-most read poet on Instagram, followed by one million people. The Tech Times adds in a parallel article that Drake is “the 7th best-selling book in Amazon's poetry category, placing himself in the company of Edgar Allan Poe and Sylvia Plath.” This is not a zero sum game. We can’t just say, naively, ‘they don’t count.’ The threat of IP cannibalizing potential readers of other poetry is real, diminishing an audience already small.

As for the ur-poem’s morphology, according to Kumar, it is de rigeur that it be Times New Roman or Special Elite type on a white background. It should ideally consist of poorly punctuated platitudes about being in love or feeling unloved. Those written with uppercase letters are verboten. It is fair, then, to simply refer to it as lower-case poetry, a poetry of typographical minimalism and barely feigned false modesty.

Kumar continues:

“Effortless and obvious in a genre known to be careful and cryptic, Instapoetry speaks to people in a way that feels like it understands them. But more important, in a way that's easy for them to understand. The most popular among these social media poets…are putting out multiple "poems" a day to the tune of tens of thousands of Likes.”

With machine-like ferocity that would put Oulipo’s automatic writing to shame, each IP poet churns out whatever words come fastest and most easily to mind, sans avant-garde playful use of chance operations. This race is dead earnest—the opposite of puckish.

Kumar:

“So when another one of these words-on-white-space poems popped up on my feed, I thought to myself: "That doesn't look so hard." It was an experiment only meant to last a few months. Instead, it turned into a year-long endeavor, 4000 followers, and ~$1600 USD in sales of a physical poetry book. In poking fun at the Instapoet, I had become an Instapoet. And it pains me to say it but, at the time, I didn’t even know it.”

Kumar made no fortune, but it’s possible he could have, had he committed to the formula, written on with gritted teeth, and followed the process to its fiduciary conclusion. What is the formula? Kumar explains:

Step 1. Create a poet persona

Use a pen name (not too many syllables or, even better, just initials).

Be elusive with your identity (never reveal your face).

employ lowercase letters only, and commas, sporadically.

Kumar emphasizes that #3 is done in order to imply (false) modesty, while in the process of accumulating thousands upon thousands of likes and trying to hustle your way to fame. For nobody likes an obvious braggart.

Step 2. Post new poems daily

Step 3. Find your fans

Step 4. Profit.

As evidence of his newfound (temporary) vocation, Kumar offers one of his Instapoems.

you wanted to netflix and chill

but i had a hulu subscription

If this is poetry, then we have all been thrown back on, not even our lovesick adolescent jottings, but something far more mindless and laughably sinister, as our paragon. Not to be left out, and as an homage to Kumar (he deserves one) my personal Instapoem offering, therefore, is this:

something starts out as a joke

and becomes the rest of your life

In closing, I will discuss briefly the curious case of e.e. cummings. The 19th century priestess of brief lines, Emily Dickinson, and possibly the least “insta” person who ever lived, had the New England good sense to use capital letters in spite of the brilliantly gossamer effects she produced. At first blush, cummings therefore would seem to be our nation’s first lower-case poet to reach high renown, in the 1960s and 1970s.

what if a much of a which of a wind

gives truth to the summer's lie;

bloodies with dizzying leaves the sun

and yanks immortal stars awry?

Blow king to beggar and queen to seem

(blow friend to fiend: blow space to time)

—when skies are hanged and oceans drowned,

the single secret will still be man

I absolve the man from lower case, on two counts. First, his poems brim with prosodic effects: consonance, assonance, rhythmic pulse, appropriate yet casual use of rhyme, mostly off-rhyme. The poem above is marked by skillful repetition (blow) to advance the poem’s essential argument. It is intensely lyric in nature, advancing us toward the poem’s final affirmation without overburdening us with rhetoric. It is a dynamic display of constant displacement. One can read him more or less as one would read a poem by Dylan Thomas or early John Keats. Its Romantic spirit is expressed with economy without the poem feeling squeezed or bare. As for mastery of rhetoric in lyric mode, its only direct declaration lies in the final line.

The second ground on which he is absolved as a “lower case poet” responsible for the IP malady, was discovered, not by me, but by the esteemed critic Norman Friedman. In “NOT e.e. cummings” Friedman, who edited multiple editions of Cummings, explains how in dialogue with editors and the deceased poet’s wife, he discovered that this poet hadn’t written his own name in lower case. Editors did that for him, or to him. This created a dilemma for the press, which didn’t know which way to go in the case. Friedman ruled to capitalize, based on evidence.

“It may at first seem of little import, but for a poet who paid such exacting attention to typography, it must be said once and for all that his name should be written and printed with the usual capital letters in their usual places: ‘E. E. Cummings.'’ Let us dispose, first of all, of the usual reaction when his name is mentioned in conversation: "Oh, isn't he the poet who never uses capitals?" Even a casual look at his poems shows that of course he uses capitals—he uses them frequently, albeit not always conventionally. The same goes for spacing, word and line breaks, parentheses, and punctuation, not to mention grammar and syntax. What probably accounts for the common misperception that he is a lowercase poet is his usual printing of ‘I’ as ‘i.’”

Through excerpts of his exchanges with editors, and facsimiles as proof, Friedman shows how he argued, with mixed success, for the restoration of the capitalized name E.E. Cummings, releasing him from the purgatory of the lower-case poet. An occasional verse strategy should not be confused with a destiny. Cummings, despite popular perception, is not the godfather of fake-modest, lower-case poetry, nor its avatar.

Nor is it just to simply blame social media itself for these ills. One must ultimately take IP seriously at least long enough to dismiss it on aesthetic grounds, rather than exempt it on grounds that it’s a harmless, hip new youth thing, a fad that will pass. The erosion is real. Its ubiquity poses a threat not lessened by its essential stupidity. At the same time, let’s remember that in mainstream poetics there’s plenty of IP equivalent to go around, lax stuff that wins prizes and makes reputations in the conventional world of poetry, and gets you that plum teaching assignment. The arbiters of Olympus are often half-asleep when they read. There are many ways to let unfiltered emotion and over-baked rhetoric take over a poem in an ephemeral show of pseudo-thought and pseudo-virtue. IP has prospered, in part, because it feeds unwittingly off a general climate of predictable and sentimental upwellings in modern poetry. If IP is them—it’s also us.

In his poem A Burnt Ship, John Donne reminds us of hidden connections that surprise us and unite us in unpleasant ways we’d rather not think about.

Out of a fired ship, which by no way

But drowning could be rescued from the flame,

Some men leap'd forth, and ever as they came

Near the foes' ships, did by their shot decay;

So all were lost, which in the ship were found,

They in the sea being burnt, they in the burnt ship drown'd.

Johnny Payne is Director MFA in Creative Writing at Mount Saint Mary's University in Los Angeles. He has published two previous volumes of poetry, as well as ten novels. In addition, he writes and direct plays in Los Angeles and elsewhere. His plays have been produced professionally and on university stages.

Read more of Johnny’s Poetry.Trois Matelots du Port de Brest, Death Letter and Natural Bridge Sweet

Featured in New Lyre Summer 2022

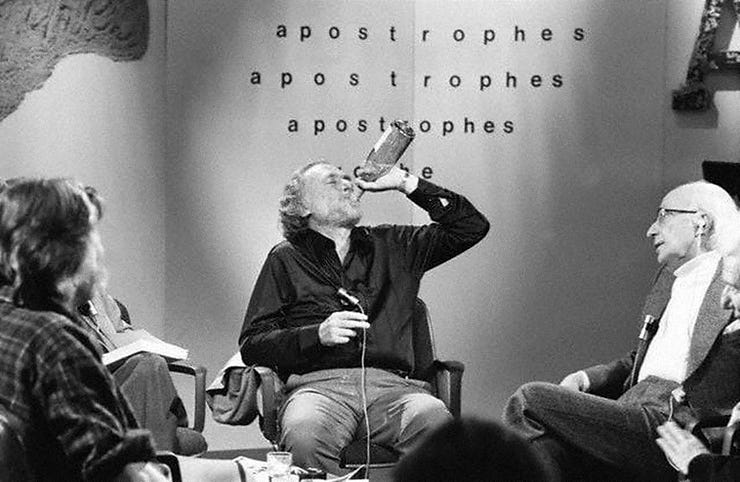

Charles Bukowski, Undisciplined Satirist

Yes, the man was prolific, having written some 5000 poems and scads of prose. Does that count as virtue, or logorrhea? I find myself wishing he’d have spent more time editing and less generating endless lines. His famous aphorism “Don’t try” too often seems to have been tantamount to “First thought, best thought.” Spontaneity has its advantages. Wordswo…

Professor Payne,

You are going to get into so much trouble for this essay, but I stand with you. As with all things, most writing is mediocre. In the publishing industry -- or in the social media sphere -- most of the readers want mediocre writing and a for-profit model has to respond to the market to stay in business. The most popular writing is the most popular writing and that's what's easiest to find.

Self-help books are the biggest sellers. It's not surprising that self-help poetry -- with its almost toxic positivity -- is what you find on IG.

I frequently wish that we could carve out our own niche, speak only to those few readers who want good poetry and can recognize it. I'm not a poet, but a literary fiction novelist, and I believe that a good novel has many of the characteristics of poetry, at the sentence level as well as at the larger structural level. Over a decade ago, I started the Dactyl Review, where only literary fiction authors can review other literary fiction authors, so that together we could create a sympathetic environment for ourselves.

I had hoped that, by designating myself literary fiction novelist, I would discourage all those fans of airport fiction from taking up my books. So far, I've been pretty successful. Reaching those readers who appreciate poetry in narrative has been harder.

You will be charged with elitism, as if hard work and talent are shameful. So be it. Take your knocks. Know that there are more people who agree with you than are willing to say so.

Poetry has always been both elitist and democratic. Indeed it's out of that very tension that poetry is born.

Shakespeare wrote for two audiences: the nobles and the groundlings. And managed to communicate to both. 'I would The multitudinous seas incarnadine Making the green one red' is the most famous example of the Bard's bearing his double audience in mind.

But even as a Rilkean 'object in itself' each poem reflects this conflict. Every poem presents us with a democracy of words because every word plays its part and is of absolutely crucial importance. Even the most insignificant 'do-nothing' word has to be carefully selected if the poem is to achieve its full effect. And very often these are the most recalcitrant.

And yet at the same time we all know that poems often take their inception from just one word. Or on the other hand that there is only too often one word that remains obstinately difficult to get right. So much so that the poem must only too often be subjected to a Valéry-like abandonment... So that that word almost bears a monarch-like to the rest of the poem. It rules over it either by its presence or by its absence. Is it any accident that Plato, himself a poet, came to think, towards the end of his life, that the best government would consist of some combination of monarchy and democracy? Certainly that's what we find in the best poems. A naturally emergent order - as opposed to an artificially imposed order - that leads to an easy-going accommodation of the democratic to the elitist. A generous and benevolent elitism in combination with a grateful and vibrant democracy. What can beat that?

'Would that all God's people were prophets,' sighed Moses. As Luther talked of 'the priesthood of all believers'. And yet thank God that isn't the case! Though nearly all are would-be prophets. One prophet for each nation in each age is surely more than enough.

For me though the great thing about poetry is that it makes full use of all the resources of the language, in a way that prose, even at its best, can simply never do. And it makes me weep to see these idiots so far gone in their asininity that they can't even make full use of the resources of prose, little own anything beyond that. Alas, their work, far from being good poetry, even fails to achieve the status of being bad prose. It simply remains illiterate muck.

As for e.e. cummings, he was special; so let the way I write his name reflect his special place in my affections. If ever anybody ever made full use of all the resources of the language it was he. I like to show that.