Featured in our New Lyre Winter 2024 issue.

Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus is one of world literature’s best-known plays. We possess it today only because scholars at the Library of Alexandria chose it as one of seven representative Aeschylus plays (out of at least seventy-three) to be copied for libraries and schools—the equivalent of choosing about four of Shakespeare’s plays. Consequently, it was re-copied in the Byzantine Empire throughout the Middle Ages, long enough for Renaissance humanists to obtain manuscripts that were eventually printed. Aeschylus’ other plays disappeared. We know them today only as titles or in short passages quoted by contemporary authors.

This was the fate of Prometheus Unbound (Prometheus Lyomenos in Greek), the sequel play to Prometheus Bound (Prometheus Desmotes). Although not chosen as part of the Aeschylean canon, the Unbound was widely read in antiquity and quoted in literary works that still survive. As a result, we have enough quotations and other information about this play to form a general idea how its plot and themes progressed.

Prometheus Unbound carries forward and completes the story of Prometheus begun in Prometheus Bound. The two plays were intended as a unity; Prometheus Bound cannot be fully understood as Aeschylus intended without some knowledge of its sequel. In this article, I translate the surviving Greek and Latin passages of the Unbound and assemble them into the framework of a proposed plot. For the portions of the play where no confirmed passages exist, I used other evidence from classical sources when available and, where all else fails, my poet’s sense of where the play’s momentum is heading.

What survives of Prometheus Unbound is fascinating. Studying, translating, and attempting to reassemble its puzzle pieces gave me new respect for Aeschylus as a playwright and for the scope of his dramatic ideas. In this article I wish to give readers some sense of what I think occurred in this lost play and how it fits into Aeschylus’ concept of the Prometheus myth. I hope I can give readers new insights into what Aeschylus intended to tell us through the Prometheus story, a story that continues to have relevance for our modern age.

Background

Before they were ever written down, the tales of Greek mythology were orally transmitted and, over many centuries and in different regions, developed multiple, often conflicting, story lines. These variant tellings gave Greek tragedians considerable freedom in molding these tales to suit their immediate theatrical needs. They also freely invented their own backstories or new plot twists whenever necessary to convey a moral or just write good theater. This is what Aeschylus did in his handling of the Prometheus story.

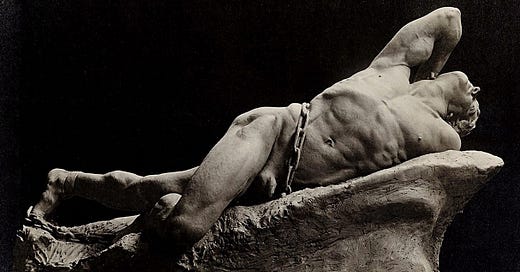

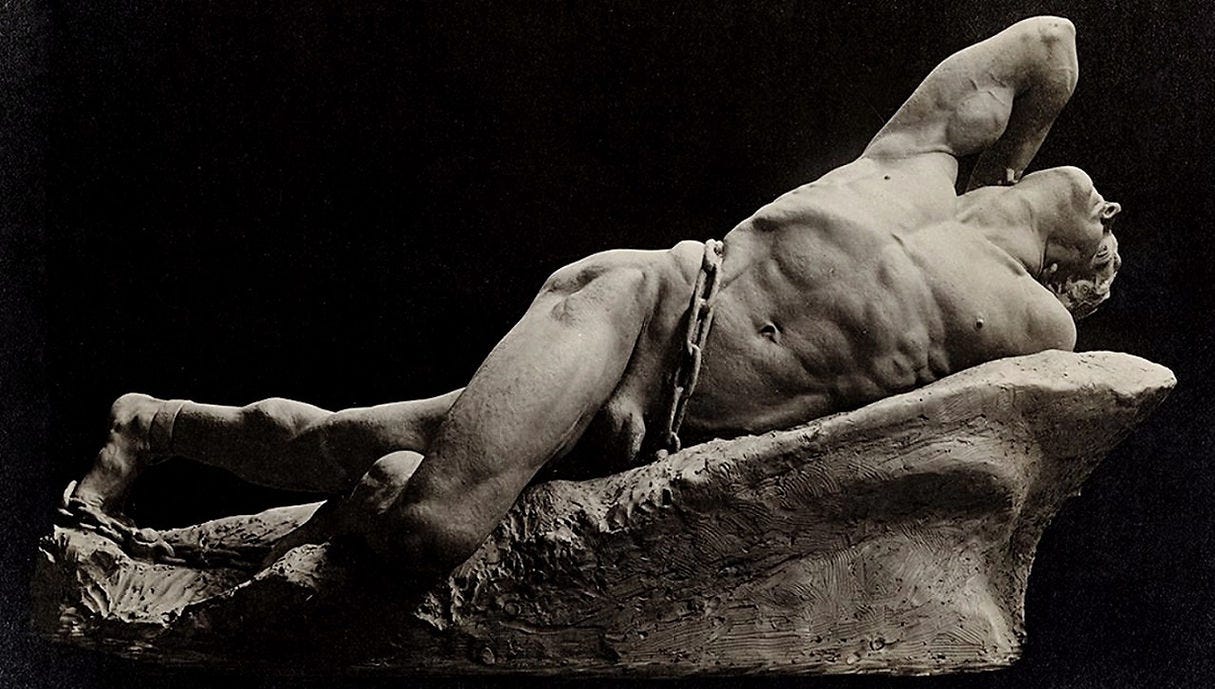

Aeschylus’ Athenian audience would already have been familiar with the Prometheus legend from Hesiod. His Works and Days and Theogony recount how Zeus overthrew his father Cronos for supremacy of the gods in an epic battle against the Titans (the “Titanomachy”). Following his victory, Zeus banished Cronos and the Titans to Tartarus. He also planned to obliterate humanity to create a new race of people. Prometheus (whose name means “Forethought”), son of the Titan Iapetus, thwarted this plan by stealing fire from Olympus in a fennel stalk to bestow on mankind. This gift allowed humanity to acquire the skills needed for survival. But Zeus’ punishment was severe. He ordered Hephaistos to chain Prometheus to a cliffside in the remote Caucasian Mountains. He then sent an eagle to consume Prometheus’ liver, which continually regenerated and was reconsumed in an unending cycle. Ages later, the hero Heracles killed the eagle and freed Prometheus from bondage. Zeus and Prometheus reconciled.

Aeschylus made important changes to this fire-legend, all of which enhance the story’s dramatic impact. Prometheus is now the child of Gaia, the Earth Goddess, a primordial deity with knowledge of the hidden workings of fate. (Her divine DNA also readily explains Prometheus’ “forethought”). In Aeschylus’ version, Prometheus was Zeus’ ally in the Titanomachy, and his counsel was decisive in Zeus’ victory. Because Zeus owed his throne to Prometheus, the punishment he later inflicts becomes an especially harsh betrayal. In addition, Prometheus not only grants mankind fire, but also teaches them the arts and sciences, enabling them to develop culture and civilization. Finally, Prometheus is now possessor of a momentous secret: he knows how Zeus will one day be overthrown, a secret he refuses to disclose even under torture. (Spoiler: Thetis, with whom Zeus desires an affair, is fated to bear a child greater than his father.) These reworkings of the legend create a dramatic tension in Bound that ultimately resolves in Unbound.

Aeschylus’ dramatic concepts were too large for a single play, so he usually wrote plays in trilogies that carried a character or legend through three successive dramas, their tragic intensity subsequently relieved by a comic satyr play. Prometheus Bound reads like a middle play: the action is already afoot, and the ending is inconclusive. A prelude seems to be called for—a play recounting the theft of fire and Zeus’ apprehension and trial of Prometheus. Yet we have no conclusive evidence from antiquity that a third play existed (or a concluding satyr play). A single line attributed to a play called Prometheus the Fire-Bringer (Pyrphoros) might refer to Prometheus the Fire-Kindler (Pyrkaeos), the satyr play appended to the Persians trilogy in 472 B.C. These descriptive suffixes were attached to play titles by Alexandrian scholars centuries after Aeschylus lived and were not always uniformly applied.

Athena - An Epic Dream I

Featured in our New Lyre Winter 2024 issue. As a twice-yearly publication, with periodic, new long-form readings, New Lyre now works by yearly paid subscriptions. Yearly subscribers get instance access to all New Lyre online content and archives (over 650 pages and 16 hours worth of reading material). Yearly subscribers (Founding Members) also receive full access to

Unlike Aeschylus’ other six remaining plays, we have no information for the date of the first production of the Prometheus plays, or if they were ever produced during his lifetime. My impression is that both Bound and Unbound were left on Aeschylus’ desk, more or less complete, when he died in Gela, Sicily, in 456 BC, and that he simply did not live long enough to write a third play. His son Euphorion, also a playwright, could have edited these two plays for a posthumous production in Athens, completing the trilogy with a third play of his own composition. Maybe this play was the shadowy Fire-Bringer. But we will likely never know the answer, and so must consider Bound and Unbound as a “duology” rather than a trilogy.

Reconstructing the Play

Prometheus Unbound was written in a structural framework typical of Greek tragedy. The action was presented in a series of episodes for actors. These episodes were separated by choral hymns sung by an onstage chorus with choreographed dancing and musical accompaniment. The speeches and dialogue of the actors were usually declaimed but sometimes sung to musical accompaniment. In addition to singing hymns functioning as interludes, the chorus also sometimes engaged in dialogues with the characters, but only rarely participated in the action.

The greatest obstacle in reconstructing Prometheus Unbound is deciding what happened during the parts of the play for which no quotations survive. Almost nothing remains of the choral songs. The middle and concluding episodes are completely blank. For these episodes, even knowing which characters appeared is challenging. In making these difficult surmises, an ancient copyist’s mistake is enormously helpful. The oldest manuscript tradition of Prometheus Bound (the 11th century Medicean manuscript) contains a dramatis personae that includes Gaia and Heracles, although neither appears in that play. We know from contemporary writers that Heracles appeared in Unbound, so it is thought that the Medicean text tradition inadvertently copies the character list for both plays. Medieval manuscripts are riddled with all sorts of copyist mistakes that hound academicians like Furies in trying to decide what ancient authors actually wrote. This particular error is indispensable in reconstructing Unbound.

When the play begins, ages have passed since the end of Prometheus Bound. Thirteen generations, per Prometheus’ statement in Bound (line 774). Prometheus remains chained to the Caucasian rocks. At some point after the first play ended, Zeus sent the divine eagle to consume Prometheus’ liver. In Aeschylus’ version, this feasting occurs every three days. The stage would depict the eagle in the background, perched on high rocks, waiting to descend again.

We do not know if Prometheus Unbound had a prologue. The first lines that we possess are from the chorus that now enters the stage. They are the Titans, the same Titans who battled against Zeus in the Titanomachy and were hurled into Tartarus following their defeat. In an astonishing act of clemency, Zeus has freed the Titans from their imprisonment. The newly-liberated Titans now make the pilgrimage to Caucasia to visit their kinsman Prometheus.

Judging from the locations mentioned in this fragment, Aeschylus placed the Titans’ exit from Tartarus somewhere south of Egypt in lands the Greeks broadly called “Ethiopia.” These lines from the entrance of the Chorus of Titans describe their route from Tartarus to Caucasia.

… beyond the Red Sea’s depths

that glitter like bronze,

Ethiopia’s sacred river, nourishing all,

and the circling streams of Ocean

where all-seeing Helios daily

bathes his immortal body,

refreshing his weary horse-teams

in gentle upwellings of water…

... by Phasis, rugged border

of Europe and boundless Asia…

we come…

to witness your sufferings, Prometheus,

the piteousness of your bonds.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Chained Muse to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.